Last week, Nick Pearce, head of the influential IPPR think-tank, argued that because of ‘fiscal realities’ it was time to rethink Labour’s approach to tackling poverty. In an article headed ‘Labour must drop its child poverty target’, Pearce, a former adviser to Gordon Brown, wrote that Labour’s anti-poverty strategy - one which involved a large hike in public spending – ‘had been running out of road even before 2008, never mind now’.

Other key Labour figures have also been raising questions about the anti-poverty strategy from 1997-2010. John Cruddas, the head of Labour’s policy review, and Liam Byrne, shadow work and pensions secretary, writing in the IPPR journal

Juncture, suggested that the 2010 Child Poverty Act – which committed governments to four separate targets for the reduction of poverty - might be seen as ‘as embodying the limits of an empirical rather than emotional approach (and has in any case been overwhelmed by the economic headwinds of the last few years)’.

These interventions come against the backdrop of the coalition government’s own attempts at a major, if yet to be completed, rethink on how to define and tackle poverty. In opposition both major parties had declared unambiguous commitments to making poverty a priority for government. As David Cameron put it, when giving the

Scarman lecture in 2006, ‘I want this message to go out loud and clear: the Conservative Party recognises, will measure and will act on relative poverty.’ Both the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats signed up to Tony Blair’s 1999 pledge to end child poverty in a generation, and both voted for the 2010 Act.

In power, such commitments have been forgotten while the coalition has effectively abandoned both the Act and its targets. This reversal is being driven by a number of themes.

First, that giving the poor more money is not an effective way of fighting poverty. ‘Over recent decades, the Left and centre-Left’s answer to poverty and inequality has been to spend more money, to redistribute from richer to poorer’ is how Frank Field put it in a piece for

The Telegraph shortly after he was appointed the government’s new ‘poverty czar’. The Work and Pensions Secretary, Iain Duncan Smith, has constantly

dismissed what he calls the ‘poverty plus a pound’ approach aimed ‘merely at lifting income over an arbitrary line’.

Secondly, that the role of income transfers should be downgraded with money redirected from benefits to improving ‘life chances’. Frank Field, for example, in his

Review of Poverty and Life Chances, called for annual above-inflation increases in child tax credits to be withheld with the savings ploughed into early years’ education.

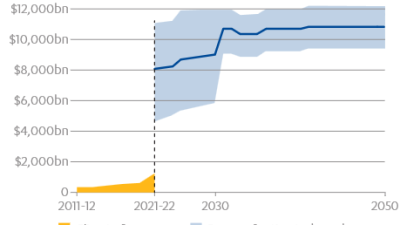

Thirdly, alongside a new emphasis on tackling the roots of poverty rather than its symptoms, the government has been attempting to redefine its causes away from broadly societal explanations – such as a lack of jobs, low wages and rising living costs – to individual ones, such as family breakdown, bad parenting and drug addiction. In 2010, it seemed that a clear political consensus had emerged – that poverty was relative, much too high and needed to be tackled by a twin-based approach – raising the income floor and focusing on prevention by improving educational and work opportunities. It was this consensus that was enshrined in the all-party commitment to the 2010 Act. While achieving its targets – such as reducing relative poverty to less than 10 per cent within a decade – were highly ambitious, the move was still a bold and unambiguous statement of intent. Indeed, at least initially, the Labour Government made significant progress towards meeting both the 60% of contemporary median household income and the low income and material deprivation targets. Relative child poverty fell by some 700,000 in the six years to 2005 before rising slightly after that. (see figure 1 in

The impact of the recession on child poverty in the UK).

Now those targets are not just being seen as unrealistic in today’s colder economic climate, the whole consensus has unraveled. It is being replaced by a very different political mindset, that the 2010 poverty targets should be dropped and the very concept of relative poverty (dismissed as a statistical construct by Iain Duncan Smith ) rethought. Ministers would love to redefine poverty downwards, simply by adopting new measures associated with lower rates of poverty.The rhetoric is now more anti-poor than anti-poverty with policy priorities redirected from maintaining the income floor (and current benefit levels) to tackling a narrow range of ‘causes’ associated with behavioural weakness (see, for example, the Government’s

Consultation on better Measures of Child Poverty).

Yet none of these arguments for change are backed by evidence. Take the claim that boosting low incomes is not the solution to poverty. A study for the Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion at the LSE on

‘Expenditure Patterns Post-Welfare Reform in the UK’, shows that the boost to low incomes up to 2005 made a big difference to deprivation levels - ‘as their incomes have risen low-income families with children increased their spending on children’s footwear and clothing, books, and fruit and vegetables, relative to other families with children, but decreased their spending on alcohol and tobacco.’

As PSE research into attitudes to necessities across the years has shown, these are all items seen by public majorities as essential for a minimum standard of living (see

Attitudes to Necessities in the UK and

Trends in attitudes to child necessities). Contrary to ministerial claims, increasing the incomes of low income families directly reduces material poverty by enabling families to afford these necessities.

The coalition’s rethink is also off the mark on causes. Drug addiction, bad parenting and welfare dependency may contribute to a degree to poverty, but the dominant explanation for Britain’s high global poverty count is to be found in its fragile and unequal labour market. One in five workers are low paid – the highest rate after the United States amongst comparable economies - and double the figure of the mid-1980s.

As the Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development has shown, there are now 45 applicants for every unskilled job vacancy in the UK – with 29 chasing every medium-skilled role. When Costa Coffee recently opened a new branch in Nottingham and advertised eight positions - just three of them full-time and all low paid – there were 1,700 applications.

Transferring money from benefits to services, by for example, freezing child benefit to pay for better childcare is also no solution. Investment in childcare, children’s centres and employment programmes are essential to improve life chances in the medium-to-long run, but if used as a substitute for cash help, would merely raise poverty in the short-term and thereby diminish the chances of successfully improving life chances in the longer term. As Alison Garnham, head of the CPAG, has argued (in the

New Statesman) pitching one against the other is not the way forward: ‘choosing services over benefits is a false choice and a progressive dead end.’

Also inherent in this new approach is the idea that using benefits to raise the incomes of poor families only results in costs and has no financial gains. Yet a

study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation has shown that reductions in child poverty have positive economic outcomes in terms of increased labour market participation as an adult, increased tax revenue and reduced benefits expenditure. It estimates the ‘GDP savings made by eradicating child poverty as somewhere between 1 and 1.8 per cent of GDP’. Welfare cuts today yield short term savings but at the expense of long term social and economic cost for the future.

The effect of the government’s ‘rethink’ is now becoming all too clear, with big implications for both the scale of poverty and the living standards of the poor. The ‘big bang’ benefit cuts from April - an integral part of the new strategy and justified in part by the arguments about income and poverty - will wipe £20 billion from the welfare bill and the pockets of the poorest. Yet this £20 billion is not being used to improve services such as access to child care, but to cut the fiscal deficit. What the present strategy adds up to is lower income ( ‘poverty minus a pound’ ) support and poorer services, while the real causes of poverty – low wages and job insecurity combined with surging fuel and rental costs – continue to intensify. As the

Institute for Fiscal Studies has shown, poverty is set to rise to close to one in four by 2020, adding 1.1 million children to the poverty count, and reversing all the gains made from 1997.

It was always the case that the Act’s targets were challenging. Few claim they are likely to be met by 2020. Of course there are difficult choices when GDP is still lower than in 2007, real incomes are back to millennium levels and the benefit bill is rising.

While it is right to recognise these constraints, that is not a reason to abandon the targets or repeal the Act. The coalition – which views the Act as a millstone – has been itching to do just this, but perhaps until now, has seen such a move as too politically explosive.

Repealing the Act would send a very negative signal, downgrading its acceptance of a societal obligation to the poor, while dropping the implicit rule that low income living standards should rise in line with growing prosperity. Without the legal pressure, the likelihood is that the UK would end up locked into a permanently high level of poverty.

If the coalition (and Labour) is serious about tackling poverty – still at levels much higher than almost all countries of comparable levels of wealth – it must stick with the Act, its principles and targets thus retaining the force of the legally binding commitment, but re-examine the timetable. This should be backed with a properly costed set of proposals which would include estimates of the relative impact of wider policies - the partial implementation of the living wage, improved child care opportunities, lower fuel and rent costs and a more targeted and effective tax system. The timetable for achieving this could then be properly set.

Condemning upwards of one in five of the population to a living standard judged unacceptable by public consensus is not inevitable or acceptable. Yet the current rethink seems to mean just that.

Stewart Lansley is a member of the PSE Research Team and the author of The Cost of Inequality, Gibson Square, 2012.

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.