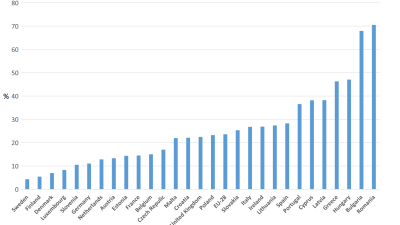

The UK-wide Poverty and Social Exclusion survey (PSE-UK) in 2012 revealed startling levels of deprivation. Eighteen million people are unable to afford adequate housing; fourteen million can’t afford essential household goods; and nearly half the population have some form of financial insecurity.

When compiling Poverty and Exclusion in the UK: the nature and extent of the problem, the first of the two-volume study based on this research, Esther Dermott and I were interested in what lay behind these top-level figures. How are different groups within the UK population affected? How do people experience poverty?

Drawing on the large-scale, representative data of this PSE-UK survey, leading experts in the field provide detailed insights into how poverty affects younger and older people; men and women; people from different ethnic backgrounds; children and parents; people with disabilities; and people in different geographical locations.

It is a stark picture: poverty, defined as those whose lack of resources and low-income forces them to live below a publicly agreed minimum standard, is affecting over one in five people – and over one in four children. Vulnerable groups are suffering disproportionately. These findings are deeply concerning; especially in light policy changes since 2012 which have already - and will continue to - push more and more vulnerable people into ever deeper poverty.

The PSE-UK approach – by combining deprivation (lacking necessities) with low-income – allows us to examine poverty in fine detail and throws light on the many ways in which poverty affects people’s lives, often obscured by less nuanced measures. In addition, the large sample of the survey - combined with the decision to interview all individual adult members of a household rather than a single household representative - has enabled us to identify new patterns in vulnerability to poverty among different groups.

Christina Pantazis and Saffron Karlsen, for example, present a detailed breakdown of the ways in which people from a wide range of ethnic background might experience poverty. Esther Dermott and Christina Pantazis show that men and women experience different types of vulnerability to poverty at different life stages. Pauline Heslop and Eric Emerson demonstrate that ‘disability’ cannot be treated as a homogenous characteristic, and people with different kinds of disability experience poverty in different ways. Gill Main and Jonathan Bradshaw disaggregate data on poverty within families with children, finding that while children are at the highest risk of poverty of all age groups, parents are likely to sacrifice their own needs to provide for children, making them even more vulnerable to lacking the necessities of life.

The book also highlights areas where more development is desperately needed: a theme running through many chapters is how to include the experiences and perspectives of diverse and heterogeneous groups while maintaining a comparable measure of poverty. Arguments are made for considering the unique situations of young people (Eldin Fahmy), people with disabilities (Pauline Heslop and Eric Emerson), and older people (Demi Patsios). As approaches to poverty measurement develop over time more groups have been represented in surveys – but there is still work to be done, for example in the inclusion of children’s own perspectives, rather than a reliance solely on parental reports on children’s experiences (Gill Main and Jonathan Bradshaw). A fuller representation of the needs, experiences and reports of these groups would further enhance our understanding of poverty and how it impacts the lives of those unlucky enough to experience it.

The UK PSE survey 2012 was conducted, and this book compiled, amidst an assault on the welfare state – in the guise of austerity politics – which have decimated the support available for those living on a low income. While we can only provide a snapshot of a single point in time, policy changes strongly suggest that if the survey were conducted today, findings would be even more stark. This poses serious concerns and questions about the effects of continued reductions in state support for people vulnerable to poverty and social exclusion.

People across the social groups examined in the volume are, among many other deprivations, going hungry, lacking adequate clothing, and living in low-quality housing which may impact their health in the present and in the future. Unsurprisingly, many of the chapters highlight the impact on well-being, both physical and mental, resulting from this. Shame is a common feeling among those without adequate resources – which is exacerbated by policy and media representations of the ‘undeserving’ poor and itself exacerbates a reluctance among people in poverty to seek the meagre and ever-decreasing state help that is available to them through the social security system.

We conclude the book with key messages for academics, policy makers, practitioners, and the media. A national reassessment of how poverty is represented, discussed, and addressed is overdue. We believe that the data and analysis presented in the volume offer valuable insight into the issues of poverty and social exclusion in the UK, and hope that the book will make a contribution to changing attitudes and, ultimately, to developing policy and practice more likely to effectively reduce and eliminate poverty in the UK.

Gill Main is co-editor, with Esther Dermott, of the first volume of Poverty and Social Exclusion in the UK and is a University Academic Fellow at the University of Leeds.

Poverty and Exclusion in the UK: Volume 1 - The nature and extent of the problem, edited by Esther Dermott and Gill Main, and Poverty and Social Exclusion in the UK: Volume 2 - The dimensions of disadvantage, edited by Glen Bramley and Nick Bailey, were published by Policy Press on November 29, 2017.

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.

PSE:UK is a major collaboration between the University of Bristol, Heriot-Watt University, The Open University, Queen's University Belfast, University of Glasgow and the University of York working with the National Centre for Social Research and the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. ESRC Grant RES-060-25-0052.